You can't teach someone to swim when they're drowning

An evidence-based case for a Secure-by-Design paradigm shift

Welcome to Resilient Cyber!

If you’re interested in FREE content around AppSec, DevSecOps, Software Supply Chain and more, be sure to hit the “Subscribe” button below.

Join 5,000+ other readers ensuring a more secure digital ecosystem.

If you’re interested in Vulnerability Management, you can check out my upcoming book “Effective Vulnerability Management: Managing Risk in the Vulnerable Digital Ecosystem” on Amazon. It is focused on infusing efficiency into risk mitigation practices by optimizing resource use with the latest best practices in vulnerability management.

There’s been an undeniable trend in the cybersecurity industry for the last 12-24 months, which involves a push for “Secure-by-Design” systems and software. While the concept of building in rather than bolting on cybersecurity isn’t new, and in fact traces back over 50 years to The Ware Report, a mounting list of massive cybersecurity incidents and data breaches has led for a renewed call for software suppliers to build products Secure-by-Design.

This push is primarily being led by the U.S. Government, with the latest U.S. National Cybersecurity Strategy (NCS) and the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), which has pursued a Secure-by-Design campaign, including a publication by the name and various alerts and blogs addressing longstanding common vulnerabilities and design flaws that still plague the industry after many years.

At its core, the push involves encouraging software suppliers to take responsibility for customer security outcomes, consider security from the onset of product development, and give it ample consideration with competing priorities which often take priority, such as speed to market and revenue.

This article takes a look at some recently published research from Daniel Woods and Sezaneh Seymour, whom conducted a meta-review of security control effectiveness. The publication is titled “Evidence-based cybersecurity policy? A meta-review of security control effectiveness”. The research was published in the Journal of Cyber Policy.

While the publication was aimed at determining the more effective security controls and providing supporting evidence to rank cybersecurity controls based on their efficacy, in my opinion it helps bolster the case even further for Secure-by-Design software and products and I’ll explain why.

Study Findings

Before diving into why I think the findings of the study support the broader push for Secure-by-Design, let’s take a look at the study, it’s structure and the associated findings.

The study acknowledges some widely known factors about the technological and cybersecurity ecosystem. The fist is that most critical infrastructure is owned by private sector entities, and those entities typically make various investment decisions related to cybersecurity based on their individual risk tolerance.

This is despite the fact that incidents impacting these entities have a broader impact, with the risk and consequences for their decisions being externalized onto a broad pool of victims.

We see this same situation when it comes to software suppliers, who make investment decisions around the security of their products based on their risk tolerance, despite incidents impacting their products having a broad impact on thousands or millions of individuals.

The study points out that commonly when critical infrastructure and entities are disrupted, citizens tend to turn to Government to mitigate those risks and consequences.

The challenge here though extends beyond critical infrastructure entities, and includes software suppliers, who’s software, products and technologies are deeply embedded into every single critical infrastructure sector, as identified by the Department of Homeland Security, as well as the broader whole of society and digital ecosystem.

Software now powers every aspect of society from consumer goods, critical infrastructure and national security systems. The entire national security and economic prosperity of the nation is embedded and powered by software.

This is supported by the fact that organizations such as the World Economic Forum (WEF) has predicted by 2025 60% of global GDP will be driven by digital platforms.

The study in question took a collection of academic studies and industry reports, 18 to be exact, to help rank security interventions (controls) by efficacy. The research they used came from academia, the insurance industry and the cybersecurity industry. The aim was to examine the statistical relationship between security controls and firm-level cyber risk outcomes in reality. The studies are cited below in the table:

The researchers synthesized all of the associated studies and identified the most effective security controls. Nine controls were identified but the top two, which we will primarily focus on, are Attack Surface Management and Patching Cadence.

Attack Surface Management

They summarized Attack Surface Management as:

System hardening

Closing ports

Complexity management

Hiding version information

Among many others.

They noted that attack surface management can be at odds with business activity and that the organizations size can also lead to irreducible attack surface size and complexity.

Some studies they use cite specific metrics such as being 5.58 times less likely to suffer an insurance claim if the organization employed “hardening techniques” and system complexity leading to higher incident costs in studies such as the IBM cost of a data breach report.

They closed out this top ranked control stating “attack surface is the strongest predictor of cyber incidents”.

Patch Cadence

Second on the list for the most effective control to mitigate risk was patch cadence, which they defined as “the speed at which security patches are applied”. Some studies they cite include one that stated policyholders with one unresolved critical vulnerability of any kind were 33 percent more likely to file a claim.

Interesting Tidbits

One interesting aspect of the study is they also found that “migrating email to the cloud was associated with reduced attack frequency”.

This comes as one of the leading cloud-based email providers in Microsoft just got completely wrecked in a Cybersecurity Safety Review Board (CSRB) report, titled “Review of the Summer 2023 Microsoft Exchange Online Intrusion” which found that Microsoft, one of the largest most pervasive software suppliers on the planet:

Suffered an incident by a nation state actor named “Storm-0558” associated with China

Experienced a cascade of security failures due to internal deficiencies

Had an compromised authentication token and signing key, permitting Storm-0558 “to gain full access to essentially any Exchange Online account anywhere in the world”

As of the date of the report, Microsoft does not know how or when Storm-0558 obtained the signing key

This isn’t to undermine Daniel Woods and Sezneh Seymour’s findings, but it is to demonstrate that again, Secure-by-Design systems, software and products will have a far better outcome on security than any single activity customers of products can take.

To point to similar situations you can look at Ivanti, Okta, MOVEit, and the list goes on - situations where patch cadence wouldn’t have matter and often consumers lacked the visibility either due to not having transparency about the vulnerable components that made up a product, or consuming it via as-a-Service, and not being able to “patch” and instead just being impacted due to an insecure as-a-Service offering, often from some of the most widely used and pervasive software companies in the world.

The Case for Secure by Design

So what does the meta-review of security control effectiveness have to do with Secure-by-Design?

The problem with the study from my opinion is that the top security controls, actually could be addressed upstream from the consumers, by the software suppliers themselves.

Let’s take a look at the top two effective security controls identified in the study and see.

Attack Surface Management

First up on the list was Attack Surface Management. This included taking steps such as system hardening/hardening techniques. While there are many definitions to this, and many of them include activities that the customer and consumer is and always will be responsible for, there is no denying that a great impact could be achieved by upstream suppliers producing secure products from the onset.

Anyone who has been in cybersecurity is familiar with implementing CIS Benchmarks, DISA STIG’s and Vendor Best Practices to “harden” a product or application to mitigate risk. This activity of course falls on the consumer, to make a product more secure and resilient against malicious actors.

It is common to have to implement “hardening guides” (e.g. CIS, DISA, Vendor et. al). However, this puts the onus on the customer to have to make a product resilient and mitigate themselves from risks upon receiving and using a product.

What if instead, we pivoted from hardening to “loosening” guides? This is a concept being advocated for by CISA in their latest Secure-by-Design publication, as described below.

Imagine if you would, a parallel example if we received a physical product, an automobile, or other examples and it didn’t just require responsible use to avoid harm but it outright required you go about hardening and securing it just to functionally use it without experiencing harm. That is the paradigm we have afoot with digital ecosystem, with software suppliers largely waiving all liability for the use of their products.

This isn’t to say that customers shouldn’t be and aren’t responsible for their overall architecture, user activities, configurations and more, but receiving products which were Secure-by-Design/Default and didn’t require significant “hardening” just to be used safely would sure go a long way, especially if attack surface management is being touted as one of the most efficacious security controls.

Patch Cadence

This is the one I particularly take issue with, or feel really bolsters the case for Secure-by-Design products and software.

There is just something painfully tone deaf in 2024 about telling customers and organizations to just “patch all the things” or “patch faster”. To see why, I will break down some metrics below.

As the landscape of digital products and software has grown, organizations struggle to keep pace with the growing number of vulnerabilities in the ecosystem. The NIST National Vulnerability Database (NVD), which is the most widely recognized and used vulnerability database in existence, continues to set records YoY for the number of known vulnerabilities, captured as Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE’s) that it reports.

As I wrote in an article titled Sitting on a Digital Haystack of Needles - it is often known that “defenders have to be right all the time, attackers only need to be right once”, and it is getting increasingly easy for them to be right, as the number of known vulnerabilities, just using CVE’s as a source, continues to grow extensively YoY.

This is emphasized by the metrics and image below from vulnerability Researcher Jerry Gamblin:

For Example:

- 2023 YTD CVE Stats:

- Total Number of CVEs: 28,261

- Average CVEs Per Day: 84.61

- Average CVSS Score: 7.13

- YOY Growth: 20.10% or +4,730 CVEs (23,531 CVEs YTD 2022)

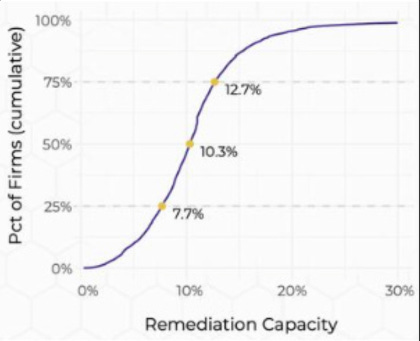

Organizations simply cannot keep pace with this explosive growth of vulnerabilities. Researchers from Cyentia Institute demonstrate organizations can only remediate about 10% of new vulnerabilities per month, while vulnerability management leaders such as Qualys show that exploitation windows generally outpace organizations ability to “patch all the things”.

Others, such as Qualys have demonstrated that malicious actors easily outpace defenders when it comes to weaponizing vulnerabilities and maximizing exploitation windows contrasted against defenders meantime-to-remediation (MTTR). (Source: Qualys 2023 TRURISK Threat Report)

Mounting Vulnerability Backlogs

Researchers from Rezilion and Ponemon have demonstrated that the average organization has vulnerability backlogs numbering in the hundreds of thousands and even millions in large complex environments.

This means organizations simply can’t keep pace with the explosion of known vulnerabilities and the associated activities of patching them, when a patch does exist. This leads to exponential growth in vulnerability backlogs, with organizations sitting on massive vulnerability backlogs sitting ripe for exploitation for malicious actors.

Knowing this, and seeing that meta-reviews of security control effectiveness are pointing to patch cadence as among the top most effective security controls what do we do?

Well, we could do what we have always done and point at finger at organizations and tell them to “patch all the things!” or “patch faster and more often!”.

However, the exponentially growth of vulnerability backlogs demonstrates that is a fools errand.

What if, instead, we pushed on software suppliers to actually produce more secure products and software from the onset, and enforced alignment with secure software development methodologies, frameworks and industry recognized standards?

Oh, you mean what if we went upstream to suppliers and drove systemic adoption of and implementation of Secure-by-Design/Default products, as opposed to victim shaming when they don’t fix someone else’s flawed and vulnerable product faster?

What a novel concept.

Conclusion

However, despite decades of systemic cybersecurity failures we continue to tell customers and organizations to get better at patching. While it isn’t explicit, what we’re telling them is to get better at fixing someone else’s flawed and broken product.

Even more troublesome, the person who provided the product is often insulated from any sort of accountability for providing an inherently flawed product to the market and externalizing the risk onto the consumers and with the increased integration of software into everything, externalizing that risk on all of society.

Insecure software is now a whole-of-society risk, not just for one enterprise, as evidenced by the mounting incidents of software supply chain attacks wreaking havoc across every industry and vertical.

The exponential growth of known vulnerabilities isn’t slowing down and no aspect of society is insulated from the prolific growth and integration of software into society.

Yet, despite mountains of evidence and data that organizations simply can’t “patch all the things!”, it remains our primary proposed advice to address cybersecurity risk?

As the saying goes, you can’t teach someone to swim when they’re drowning, and right now organizations are drowning in insecure products and software.

Telling them to “just swim faster” isn’t going to work.

There has to be a better way.

There is a better way.

And it starts with holding product and software suppliers accountable.