Going Down With the Ship

A look at the acceleration of digital vulnerabilities and organizational and societal challenges to deal with them.

We’ve recently discussed the state of the vulnerability management ecosystem. We touched on a report from Rezilion and the Ponemon Institute showing that the more than half of organizations have more than 100,000 open vulnerabilities in their backlog, a number that leaders such as Equifax CISO Jamil Farschi estimated is low.

As we have discussed repeatedly, as society continues to rush headfirst into digital transformation and utilizing software to power everything from personal leisure to critical infrastructure and national security, the proliferation of vulnerabilities will only grow.

For example, we know that MITRE published over 25,000 vulnerabilities into the NIST National Vulnerability Database (NVD) in 2022. However, as discussed by researchers in the recent Exploit Prediction Scoring System (EPSS) whitepaper titled “Enhancing Vulnerability Prioritization: Data-Driven Exploit Predictions with Community-Driven Insights” research tracking exposed vulnerabilities at hundreds of companies that the monthly median remediation rate was only 15.5%, with 25% of companies remediating less than 7% of open vulnerabilities.

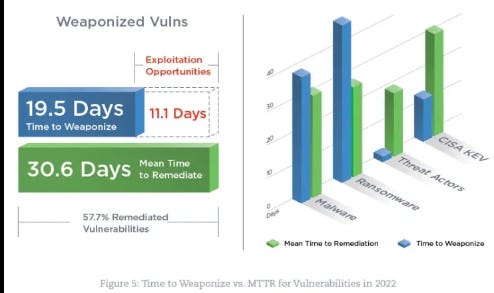

This research aligns with other research we’ve cited from organizations such as Qualys and Rezilion in past articles, which points out that it takes malicious actors less than 20 days to weaponize vulnerabilities for exploitation but organizations over 30 days as a mean-time-to-remediate (MTTR), with almost upwards of 40% of vulnerabilities never being remediated period.

This acceleration of discovered/published known vulnerabilities, coupled with most organizations inability to properly prioritize them for remediation and having sufficient resources to address them leaves organizations in a situation where they’re trying to save a sinking ship by removing water with a bucket.

The unfortunate reality is that vulnerabilities are emerging faster than organizations can make sense of them and while innovative solutions such as CISA’s Known Exploited Vulnerabilities (KEV) catalog and the Exploit Prediction Scoring System (EPSS) are gaining ground, our current remediation capabilities are significantly outpaced by malicious actors abilities of weaponization and exploitation.

This means the backlog of unmitigated/un-remediated vulnerabilities continues to grow exponentially over time.

While there is of course the promise of Artificial Intelligence (AI), the truth is that malicious actors have, and are, more effective at adopting emerging technologies than defenders.

As security practitioners and as an industry, our visceral reaction to this reality is to “scan all the things” and just throw the toil over the fence to Developers to deal with, all with little to no context or guidance to help facilitate prioritization and effective use of scarce resources.

As we have covered in previous articles, this is akin to security establishing “gates” to block deployments and builds and throwing context-less vulnerabilities over the fence. This leads to resentment, shadow IT and ultimately fosters silos between Developers, the Business and Security, all of which is antithetical to the entire concept of DevSecOps, which ironically seems to be an industry focus at the moment.

We also have a tendency to think of Security as something we can buy, with adding new tools and features, but as my friend Ross Haleliuk of Venture in Security points out, security is a process, not a feature. It is therefore something you practice, not something you reach as a destination.

Yet as an industry, we continue to throw our resources at tools, thinking if we just add more security tools to our portfolios as cybersecurity leaders, this will fix the problem.

However, as I have written about previously, citing industry research from organizations such as Ponemon, the average organization has over 40 security tools, with security team members attesting that the tools aren’t properly configured, implemented, monitored and are simply adding to their already cumbersome cognitive load.

No system or software is infallible and of course we are hearing calls for “Secure-by-Design/Default” software/systems, such as CISA’s publication by the same name, which we have covered here.

However, despite Cybersecurity’s role being to prevent material impact of a security incident, as discussed by longtime industry leader Rick Howard in his Cybersecurity First Principles book which we covered here, and Malcom Harkin’s ICIT whitepaper on material risk titled “Materiality Matters”, the uncomfortable truth is, as I have said previously, we are shouting into the void until incentives, market regulatory measures and commensurate consequences manifest.

The concept of building security in, versus bolting it on is literally over 50 years old, with origins back to The Ware Report. As we’ve discussed, the market failure of cybersecurity won’t resolve itself on a voluntary basis.

The famous Albert Einstein once quipped “The definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different result”.

Yet as an industry we’ve spent 5 decades doing the same thing, expecting a different result.

This includes thinking we can fix things with more tools and recommending what businesses and organizations “should” do. The most recent example is the CISA Secure-by-Design/Default guidance using the phrase “should” 51 times, as we cited in our article “The Elusive Built-in not Bolted-on”

Surely they will listen this time, right?

They say in life you get what you tolerate, and as a society, we’ve tolerated vulnerable by design products, technologies and software for decades, so that is exactly what we will continue to get, consequences be damned.

We continue to look for more efficient ways to make sense of the never-ending onslaught of software/technology vulnerabilities, to some extent aided by the longstanding reluctance to make security a subset of quality, that is built in as part of the product/system development lifecycle (SDLC).

Millions of sensitive records and data continue to get exposed, stock prices go on unimpeded, financial regulatory consequences are paltry in comparison to revenues (lender OneMain, an organization with $4 billion USD in annual revenues, was fined $4.25 million for cybersecurity lapses) and the world keeps spinning.

However, as software continues to get integrated into our most critical systems and institutions, including cyber physical systems, and playing an increasing role in geopolitical conflicts and national security (Microsoft recently identified targeting of US critical infrastructure by China), the potential ramifications exceed exposed records and include life, limb, societal stability and global power dynamics.

Will we change our approach, or continue down the path that has led to our current abysmal track record, deluding ourselves into thinking the same historical approaches will yield a different desired outcome?

Time will tell, but for now, we seem committed to going down with the ship.