Since we on the verge of the inaugural Cyber Defense Matrix Conference, which I am thankful to get the opportunity to attend, I figured I would write an article about the Cyber Defense Matrix.

This article may be helpful for both those new to the concept as well as those familiar with it but interested in a refresher.

For those unfamiliar, the Cyber Defense Matrix is a tool, framework, or mental model depending how you look at it, created by Sounil Yu.

It is of course, also a book, which is available on Amazon.

Sounil currently serves as the CISO and Head of Research at Jupiter One. Prior to J1, Sounil held roles such as the Chief Security Scientist at Bank of America and CISO-in-Residence for YL Ventures.

Why does this matter?

Before diving into the Cyber Defense Matrix itself, let’s discuss why it is relevant and necessary.

If you’ve been in the cybersecurity industry for any amount of time, you have likely learned some fundamental truths. Among those is the reality that we have a tool sprawl challenge when it comes to the tooling and vendor ecosystem, as well as internal to our own organizations and cyber portfolios.

To put the problem in perspective, one recent example is a Cyber Scape map Ross Haleliuk shared in a recent issue of his “Venture in Security” substack (which I strongly recommend subscribing to if you haven’t already).

To put it lightly, the map and security vendor ecosystem is complicated.

The map plots the existing security vendor ecosystem across various capabilities and speciality areas, drawing from insights from Research Analyst Richard Stiennon’s “IT-Harvest Dashboard”, which is the largest cybersecurity vendor database. The map demonstrates 3,231 companies across 17 categories.

Ross breaks down why there are so many security vendors in the above mentioned article, citing reasons such as the size of the market opportunity, diminished company failure rates, a continuous influx of capital and more.

All of this culminates into a complex ecosystem of security vendors and tooling.

This challenge exists in a big picture sense across the industry as a whole but often also exists on a smaller scale within individual organizations, as the CISO and security teams look to bring various tools to address the ever changing threat landscape they are faced with on a regular basis.

Studies from sources such as Poneman found that on average companies are deploying 47 different cybersecurity solutions despite only 53% of IT experts admitting they know how well those tools are working.

Other sources, such as Market Cube in their “Security Technology Sprawl Report” found that security teams are struggling to implement all of the tooling, with 71% of respondents saying they are adding tools faster than they can manage and productively use them and the burden of tool maintenance is compromising their threat response capabilities. The study touches on the cognitive overload associated with security tool sprawl and the implications for organizational security posture and incident response.

This problem exists at the macro level in the industry as well, with a dizzying array of security tools from both vendors and the OSS community for organizations and leaders to make sense of and rationally integrate into their portfolios. This leads to confusion, frustration and often poor decisions, further compounded by unclear and buzz word-driven marketing tactics.

One other fact to consider is that security tools are part of your attack surface, a point too often overlooked in the security community.

Whether proprietary self-hosted vendor solutions, OSS or as-a-Service offerings - all of these are part of your software supply chain and can and have been targeted and weaponized by malicious actors. This fact is even more concerning when you realize that security tooling often has elevated privileges and access, falling into what NIST would define as “Critical Software” in their software supply chain guidance.

There is an uncomfortable irony in the fact that in our pursuit of improved security outcomes and reducing organizational risk, we ultimately end up doing the opposite and increase attackers chances at success and decrease defenders effectiveness by drowning in security tool sprawl, capabilities gaps and an inefficient application of finite resources and attention.

Some security leaders, such as Mark Curphey of OWASP fame have recently published pieces predicting that “a security tools crash is coming”. Mark cites reasons such a security teams wanting less tools, more vendors than the size of the market can support and changes in the venture market. One interesting thing to do is to contrast Mark’s stance in his article with Ross’s, since they paint somewhat different perspectives on the future of the security vendor ecosystem.

Nonetheless, let’s move on to the actual Cyber Defense Matrix itself - which is our focus here.

The Cyber Defense Matrix

Now that we have a bit of the “why” out of the way and an understanding of the sprawling security tool/vendor challenge, let’s discuss the Cyber Defense Matrix, its components and how it can be leveraged at both the micro level within an individual organization, as well as at the macro level across the entire ecosystem and industry.

Source: https://owasp.org/www-project-cyber-defense-matrix/

The Cyber Defense Matrix provides a framework to make sense of the security vendor and tooling ecosystem. It also provides a useful approach for security teams and leaders to rationalize their security tooling portfolio, identify duplicative capabilities, gaps and unmitigated risks.

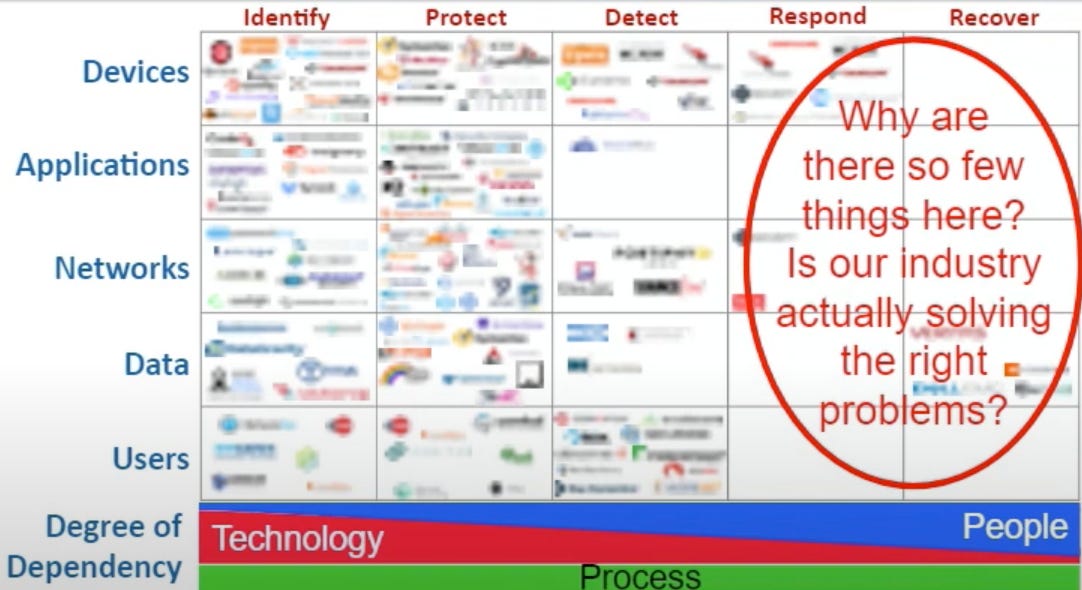

One key aspect of the matrix is that it builds on an approach most in Cyber are familiar with, which is the NIST Cybersecurity Framework (CSF). The five operational functions it uses are Identify, Protect, Detect, Respond & Recover.

It then builds on these functions by examining five asset classes, which are Devices, Applications, Networks, Data & Users.

Ultimately these five functions and asset classes are placed into a 5x5 two dimensional matrix.

At the base of the grid are the quintessential triad of People, Process and Technology, with an appropriate reference to show the degree of dependency that each of the respective cells have on the triad.

One thing I also love about it is that process is the bedrock of the entire model. In a recent LinkedIn post I made the case that process is the forgotten middle child of the People, Process and Technology triad. I say this because it is often overlooked among the other two peers despite being what drives tooling and configurations and also being what people align with and model behavior after.

Sounil describes the two dimensions of the grid as a mental model of things we care about (nouns) and things that we do (verbs). On the left we have the things we care about and across the top of we have the things that we do.

Sounil delivered a DEF CON talk in 2021 where he mapped common security capabilities into the matrix, showing where specific capabilities or tooling fits across the functions and asset classes.

You’ll notice that the overwhelming amount of capabilities and tooling fall in the first 3-4 columns and very minimally in the last, which is recover.

Sounil also delivered a CNCF Cloud Native Security Day talk where he uses a version of the matrix but this time maps specific security vendors from the ecosystem to the matrix and you’ll notice the results are very similar.

(Vendors blurred intentionally for neutrality)

The degree of dependency is intentional in the matrix to point out that we have a much greater dependence on technology to Identify, Protect and Detect while we have a more human-centric necessity when it comes to Respond and Recover.

In the CNCF talk Sounil raises a good question, which is why are so few vendors and technologies looking to solve or function in the Respond and Recover pillars. The question is particularly sobering when we all reflect on the common adage in cybersecurity which is “its not if, but when”, alluding to the fact that nearly all organizations will experience security incident(s) on a long enough spectrum of time.

Couple that with the often cited trope of “it’s people, process and technology in that order” and the unfortunate reality that organizations historically invest in technology over people, and it is easy to see why the “when” happens, things will be painful due to a disproportionate investment and focus.

Sounil goes on in the CNCF discussion mentioned above to discuss the characteristics of the solutions and capabilities that do help Recover, which he dubbed the “DIE Triad”, to represent Distributed, Immutable and Ephemeral (an obvious play on the longstanding Confidentiality, Integrity and Availability triad).

I won’t dive into the specifics of the DIE triad in this article, but I highly recommend digging into the above talk and DIE triad if you have an interest in building modern resilient digital systems.

So not only does the Cyber Defense Matrix provide an interesting and concerning insight into our capabilities and vendors in terms of alignment with the CSF function as an industry but it also serves as an incredibly useful tool for security leaders and teams to examine their tool/product portfolios and perform various valuable activities.

As Sounil points out, these include more efficient resource allocation, perform portfolio gap analysis, create tech roadmaps and understand organizational handoffs, where risks can manifest if not done properly.

In an industry flush with noise and confusion when it comes to vendors/OSS tooling, capabilities and emerging threats, the matrix provides a concise and logical construct for leaders to understand their portfolio, properly allocate resources, maximize efficiencies and address gaps.

One thing that is clear from the matrix as well is that we have gaps in our capabilities that facilitate recovery as well as investing in the key resource (people) that make recovery possible.

This is a painful reality that many organizations have and will learn as incidents unfold and that society may even have to reckon with due to exponential levels of systemic risk that have sources such as the World Economic Forum (WEF) predicting a significant cyber incident will occur in the next 24 months.

Much like the matrix scene itself with Neo and Morpheus that is now famous - as an industry and organizationally, we can take the blue pill and continue down the path we’re on, or we can take the red pill and come to terms with our gaps both internally and systemically and work to address them.

The choice is ours.